Written by Victor Evink

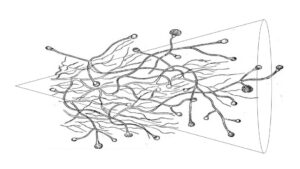

We tend to think in the singular: ‘the’ future. But that is misleading because, in a sense, the future is substantially different from ‘the’ present or ‘the’ past. After all, those are already here. And apart from ideas about a multiverse, where endless timelines coexist and you in another universe are not sitting reading this article right now but are still just finishing that e-mail, both are just one of those. But ‘the’ future does not yet exist, and that is liberating because it means many possibilities are still open. That is why the field that professionally deals with the future is called ‘futures studies’, in the plural: the study of possible futures - some more likely than others, admittedly.

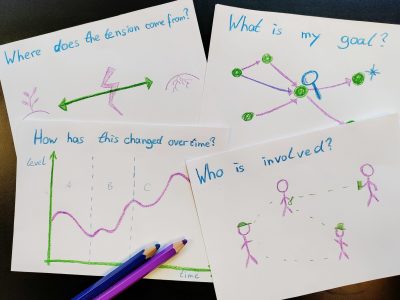

‘Futures studies’ asks roughly three things: 1.) what are the limits to possible futures that could emerge? 2.) which futures are more likely than others and why? and 3.) what futures do we find desirable and how can we ourselves influence this process? How professional futures forecasters do this, and how I apply it myself, I hope to make a little clearer in this article.

The butterfly effect

Predicting the future could be understood very mechanically, like the weather: a week in advance is still reasonably doable, but the further away, the less accurate it becomes. Sometimes minute differences can have a big impact in the long run. We call that the butterfly effect, a term most people will know from the (incorrect) anecdote from Jurassic Park that a butterfly in Brazil could cause a storm in California. Weather can affect the outcome of a battle, or how many people show up at a demonstration, which will eventually lead to a revolution.

It raises the question of what kind of world we would have lived in if history had turned out differently. What if Germany had won World War II? Or if a nuclear bomb had been dropped in the Cold War? There were electric cars in the late 19th century, but with the dominance of the emerging oil industry, they were all but forgotten. In the 1970s, it was not at all a foregone conclusion that everyone would one day have their own computer, until Bill Gates managed to convince the masses of that. Apple would later do the same for the smartphone, and now Mark Zuckerberg is trying it with ’the metaverse‘.

More subtly still, it is in the area of ideology and values, beliefs about what life should be like and how we should treat each other. What is our relationship with the earth and life on it? How do we distribute our wealth? How do we shape political institutions? How do we view religion, tradition, gender, ethnic and sexual diversity, or family structures and relationships? Different views on these can also (metaphorically, and occasionally even literally) be at war with each other, and in many cases are not yet a foregone conclusion.

The torch

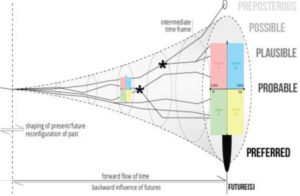

One way of mapping these things is the future torch, a now classic method in the field of futures studies. Imagine a torch with which you walk through a forest in the dark. The torch casts a beam of light in front of you, bright and sharp in the centre, but increasingly blurred at the edges. Similarly, we look into the future with our imagination. The light source is the present and we move in one direction. The closer to the centre of the beam - or the more in line with the direction we are currently moving - the better we can imagine a particular future. Here you could also include quantitative futures research, where calculations are made with models often based on the present and recent past. These can sometimes predict the near future very accurately, but they do not deal well with unexpected and especially fundamental changes. The further from the middle, the more absurd a picture of the future appears to us. Everything outside the bundle lies in the darkness of the unthinkable. This does not mean it is utterly impossible, just that we cannot imagine it at the moment. But, as we walk further and turn in a certain direction, the direction of our field of vision changes and completely new things suddenly become imaginable.

Playback

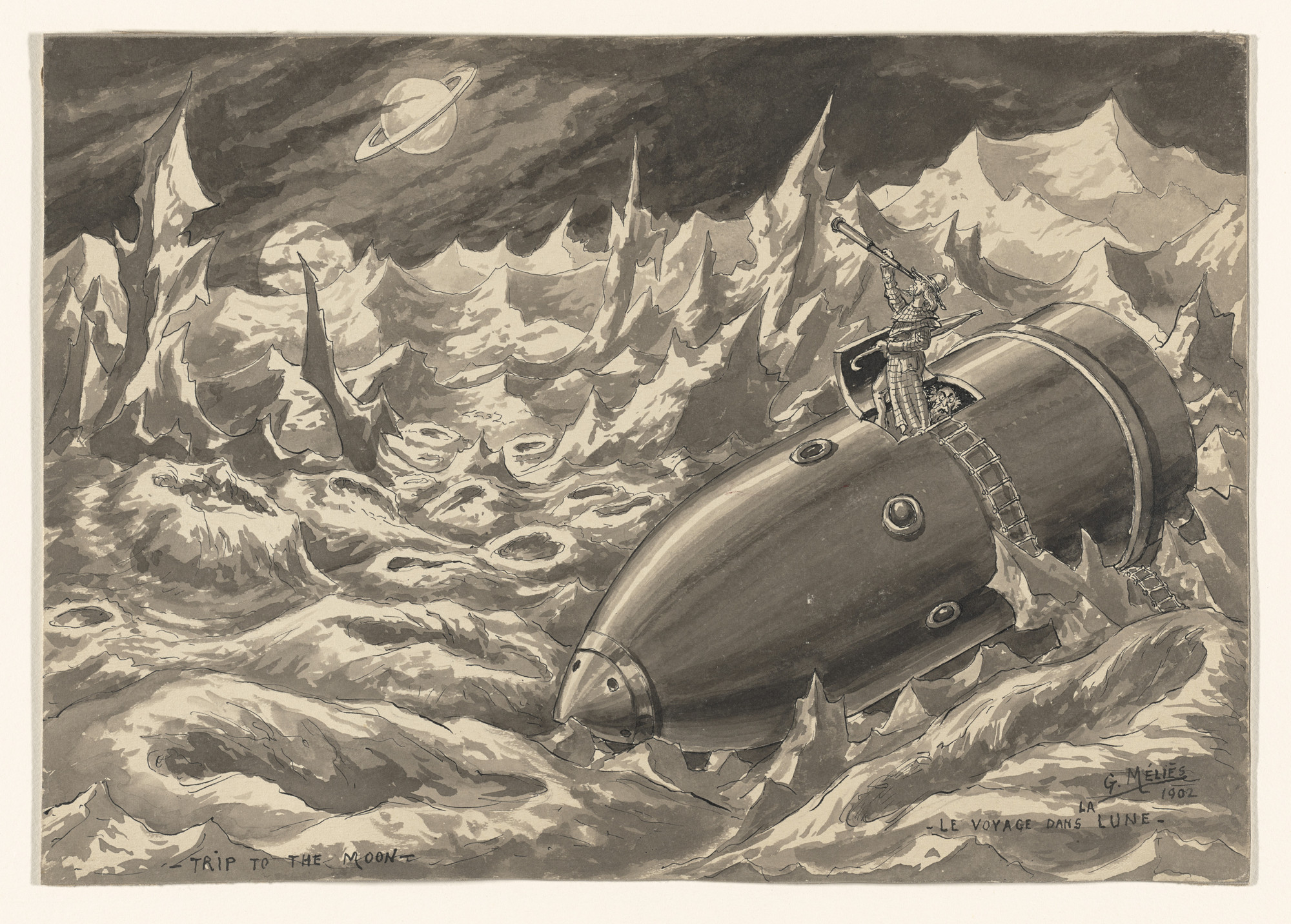

As I mentioned in my earlier article ‘Future plants‘ have described, describing and framing images of the future in science fiction has an influential and sometimes even decisive effect on the eventual course of history - think, for example, of Jules Verne's books. One could say that not only the past, but also (our image of) the future influences the course of the present. A potential future can manifest itself not only in a physical place, but also in thoughts, expectations and ‘frames’ that spread in the collective consciousness through stories and images.

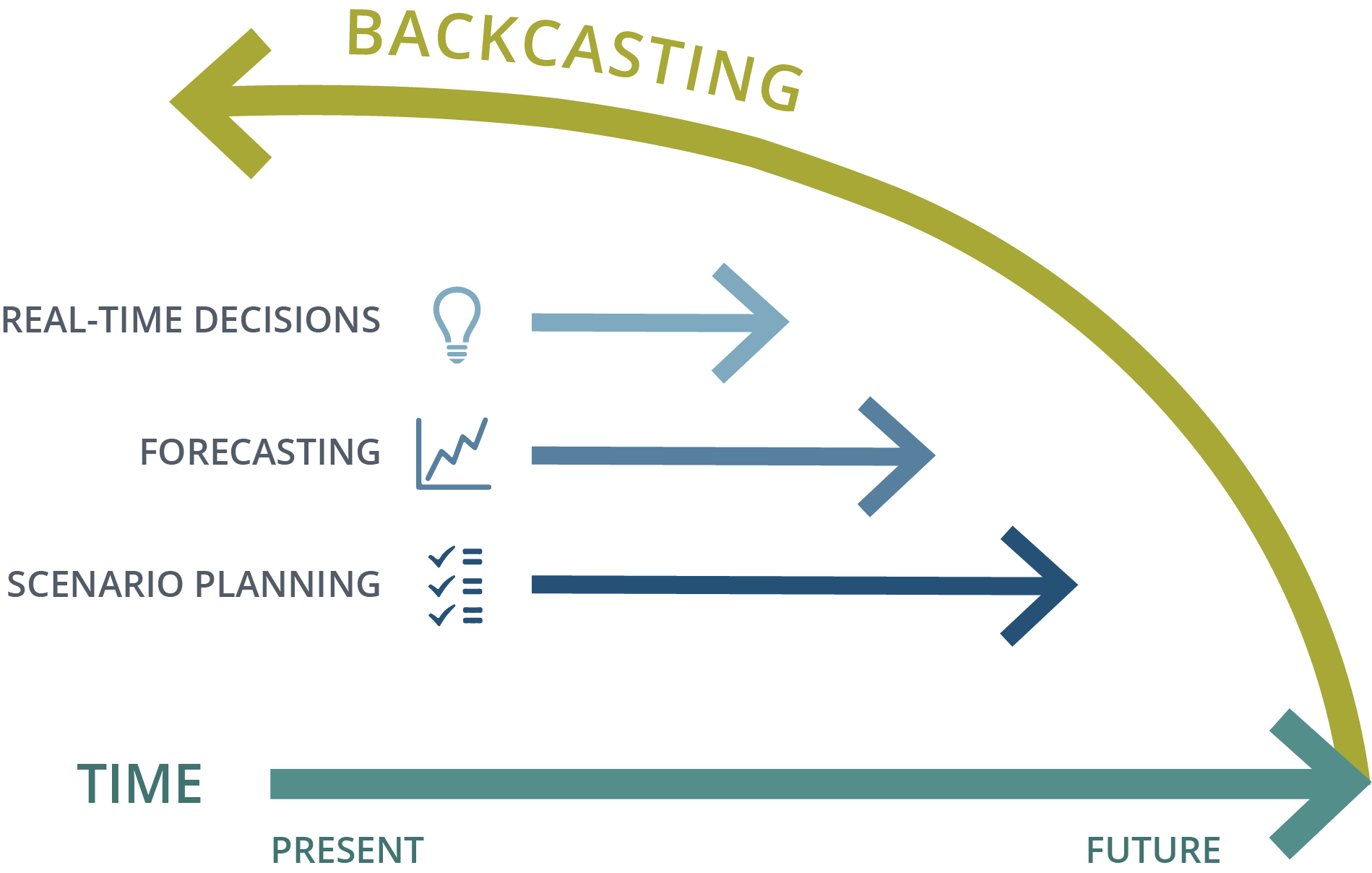

The future predict is therefore often a matter of examining fictitious images of the future and then taking those replay (English: backcasting): what steps would be needed, in different areas (social, ecological, etc.), to arrive at a speculative future world from the present? This can make it clear in which areas the present can be adjusted to prevent a dystopia or, on the contrary, to bring about a desired future. But how do we know where we do want to go?

Backtracking is determining the intermediate steps needed to arrive at a fictional vision of the future. This can be either one we want to achieve (utopia), precisely one we want to avoid (dystopia), or something in between (ambitopia)

The compass for the future

The future compass is actually a joke. A parody of the political compass, it presents 4×4 scenarios that differ from each other on two axes. Whereas the ordinary political compass maps the location of voters, politicians and parties on the axes ‘authoritarian - libertarian’ and ‘left - right’, the axes on the compass of the future can vary. This gives concrete expression to the extremes of conceivable possibilities, such as ‘harmonious - chaotic’ or ‘high-tech - post-apocalyptic’.

Although most future compasses are nothing more than an amusing hobby for nerds, it is still interesting that the most insane and abstract descriptions are captured in a picture: a small glimpse that still evokes a certain feeling. In that way, it can indeed be a serious method of asking what kind of future we would like and why. What does the living environment look like? What messages does such a society send out about itself, possibly without the people living in it being aware of it? How do people move through such a world? Imagining answers to these questions creates experienceable glimpses into these possible futures.

Futures

The way we imagine these glimpses never becomes completely objective. This is because what attracts or repels us in images of the future has everything to do with our own inner experience and psychology. What is freedom, or security, for you personally? What drives you in the things you do or pursue? How much do you trust people, or systems, and why and when not? And, as a corollary: what ideas about what the world should look like do you like, or dislike? Have you ever wavered, or changed your views? As such, possible futures turn from abstract images and science-fiction films into personal, inner desires, fears and ideas that dance around us in the here and now, giving us hope and guidance, either making us angry, or scared. How can we learn to rise above these emotions and influences and reflect on what sets us in motion, and then make a more conscious choice?

In this light, imagining and playing back images of the future belongs as much in psychology and spirituality as on the drawing boards of professional science-fiction authors, designers and futurists. It concerns us all. In fact, you could put the future compass over the light cone of the torch and see every movement, up or down, left or right, as an inner journey towards the future.

With this, the future becomes an active verb, what Professor Maarten Hajer of the ‘Urban Futures Studio’ in Utrecht calls “futures” (in English: “futuring”): the collective and individual creation of images of the future. The more people actively do this, the more the future lies open. We pave the way ourselves.

Spanish poet Antonio Machado (1875 - 1939) already understood this:

Traveller,

there is no way

the road you make yourself, by going.

Everything passes and everything stays,

but it is up to us to go,

moving on and paving roads,

roads across the sea.